The Bohemian Trade Route — A History-Shaping Phenomenon

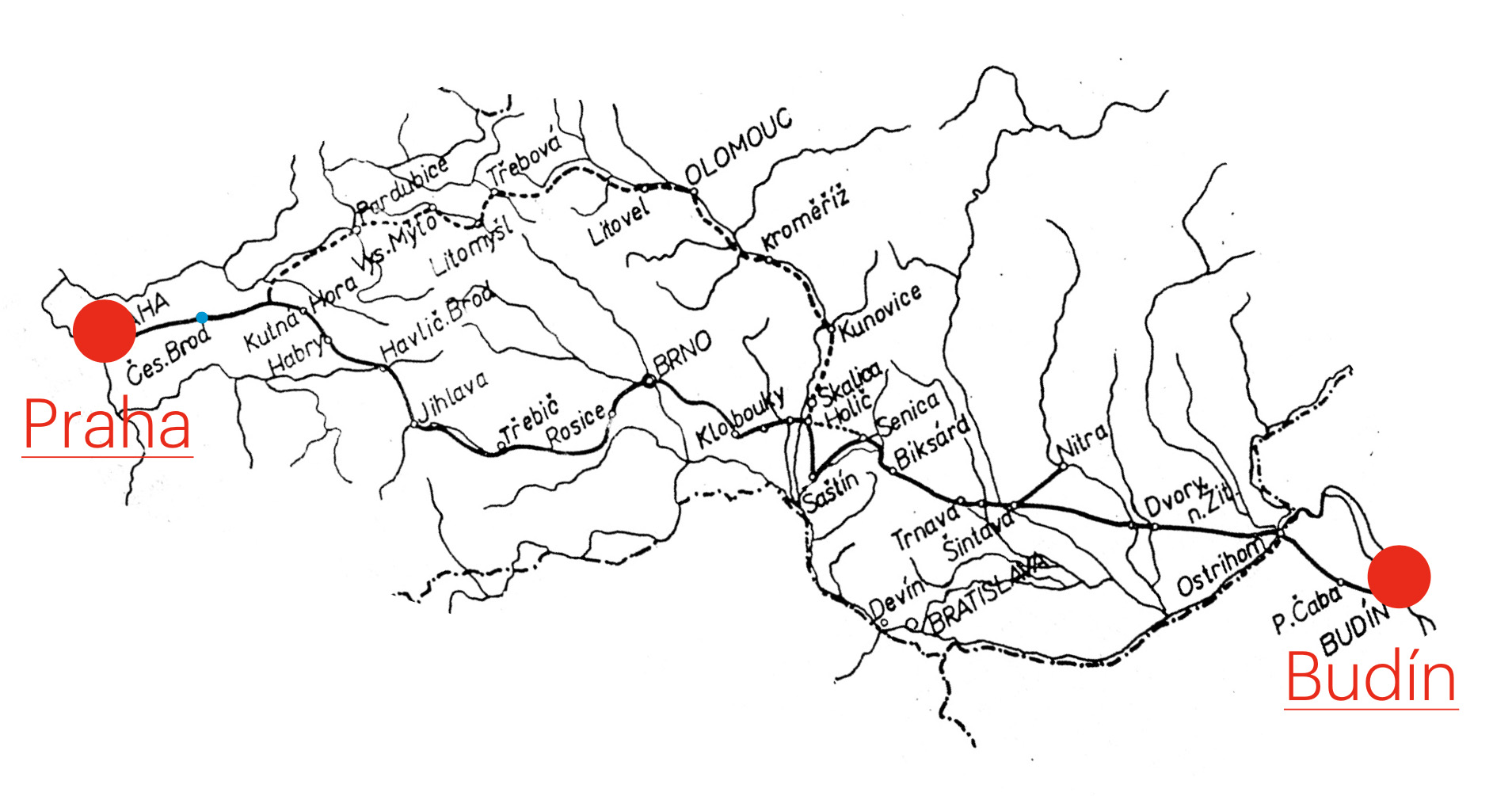

The Bohemian Trade Route connected Prague with Buda during the Middle Ages. It was part of a much longer European trade route stretching from Southeastern Europe all the way to the shores of the Atlantic Ocean.

This royal road was officially established by the Hungarian King Charles Robert of Anjou and the Bohemian King John of Luxembourg during a meeting at Vyšehrad in late November 1335, where they agreed on commercial cooperation. The official route on the Hungarian side was confirmed by a charter issued by Charles Robert on January 6, 1336, following the same path that had already existed during the reign of Béla IV.

Pohľad na gotickú Prahu v 15. storočí. Norimberská kronika r. 1493

The Historical Development of Long-Distance Routes

Long-distance trade routes connected distant economic and socio-cultural regions. At first, they were merely beaten paths dating back to prehistoric and ancient times.

Later, with the use of draft animals and carts, they turned into rutted tracks without stone foundations or any kind of surface treatment.

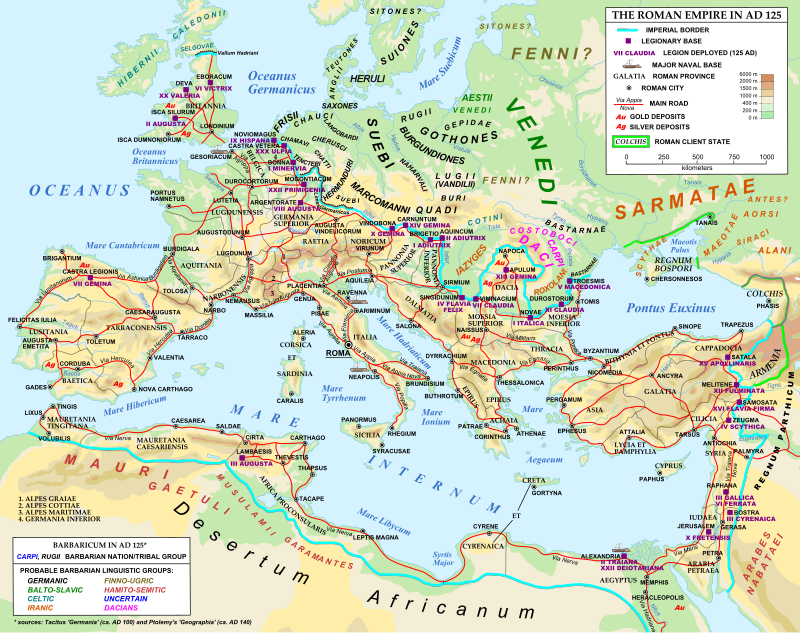

The level of road construction significantly advanced in antiquity thanks to the highly developed civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, ancient Greece, and the Roman Empire. However, with the decline and collapse of these civilizations, the quality of the roads deteriorated.

In times of peace, long-distance routes served for intercity and international trade and the exchange of goods. During times of war, they enabled swift military movements and campaigns. Already during the Roman period, these roads were accompanied not only by a network of relay and resting stations but also by defensive fortresses and guard castles.

- The First Road Constructions

- Roman Roads

- Via Appia

- Amber Road

Rozvinutá cestná sieť v Rímskej ríši

Via Appia

The First Road Constructions

The earliest roads were built in the 4th millennium BC in Mesopotamia. One such road is known near the ancient city of Ur. Archaeologists have also discovered ancient roads on the British Isles, such as a track located near the present-day town of Glastonbury.

Another of the oldest roads in Europe is the Sweet Track, also found in the British Isles. Constructed at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, this road was made from ash, oak, and lime wood planks. Among the oldest paved roads are those found on the island of Crete, covered with limestone slabs and dated to the 3rd millennium BC.

Bricks were first used for paving roads in ancient India around 3000 years before the Common Era. The expansion of the road network was closely linked to the introduction of wheeled transport.

In ancient states, the construction of roads was crucial for the movement of armies, the administration of empires, the transmission of information, and the organization of trade. Paved stone roads began to appear in Mesopotamia and the Achaemenid Empire. Special units, part of the Assyrian army, were also involved in building bridges and roads for war chariots.

During the reign of Darius I (522–486 BC) in the Achaemenid Empire, the famous Royal Road was built, connecting Ephesus and Susa, spanning a distance of 2,700 kilometers. Along the route, 111 relay stations were established. Royal couriers could deliver a message from one end of the road to the other in as little as six days.

Under the rule of Qin Shi Huang (210 BC), the founder of the Chinese Qin dynasty, a network of roads was constructed with a total length of 7,500 kilometers. These roads were 15 meters wide with three lanes, the central lane being reserved exclusively for the emperor.

.

Roman Roads

From the very beginning of their rise to power, the Romans built an extensive road network. At the height of its development, the Roman Empire operated 29 radial long-distance military roads, all radiating from Rome.

What made these roads remarkable was the Romans’ preference for straight routes with minimal curves. The empire's 113 provinces were interconnected by 372 roads, forming a web that enabled the rapid movement of military units, the efficient administration of the empire, the transportation of goods, and the swift delivery of messages. Emperor Octavian Augustus established an imperial postal system. Couriers delivered mail across the empire, and under favorable conditions, they could cover around 75 km per day using freight wagons.

In 20 BC, Emperor Octavian Augustus commissioned the construction of the Milliarium Aureum, or Golden Milestone, near the Temple of Saturn in Rome. This marble column, covered with gilded bronze, listed all the major cities of the empire and their distances from Rome. The Golden Milestone is linked to the famous saying: All roads lead to Rome.

The total length of the Roman road network is estimated at around 400,000 kilometers, of which approximately 80,000 kilometers were paved roads across Europe, the Near East, and North Africa.

These roads had their own names. In Gaul alone (covering roughly the territory of modern-day France and Belgium), it is estimated that around 21,000 kilometers of roads were paved. In Britain, at least 4,000 kilometers were constructed.

However, these paved roads were not for everyone. Only soldiers, high-ranking imperial officials, couriers, and those granted special permission were allowed to use them. The rest had to travel on winding and unpaved paths leading alongside.

The Romans were skilled road builders, paying close attention to quality. Even by modern standards, Roman roads were massive infrastructure projects. From the mid-5th century BC, road construction was governed by Roman laws, especially the Law of the Twelve Tables, which regulated public works, including roads and bridges.

According to Roman law, roads were required to have a minimum width of 2.4 meters on straight sections and up to 4.9 meters in curves. Over time, this width increased to between 6 and 8 meters, about half of which was reserved for sidewalks on both sides of the road.

Roman roads were built in multiple layers, using mainly local materials. Detailed studies of preserved sections have shown that there was no single standard method of construction. The Romans adapted their techniques based on available materials and the specific terrain where the road was being built. Typically, the roads were composed of several layers (usually three).

On the prepared foundation, they first laid a layer of stones, followed by a layer of gravel, and then a layer of coarse sand, often mixed with a binding agent forming a lime-based cement. The top pavement consisted of well-shaped basalt or other stones, sometimes sealed with cement mortar. Estimates of the total thickness of the road body vary but were usually up to 1.5 meters. The upper layer ranged from 5 cm to 60 cm in thickness. The road's cross-section was convex, allowing rainwater to drain quickly.

As mentioned earlier, many Roman roads had specific names. The oldest Roman roads include Via Appia (312–264 BC) and Via Flaminia (220 BC). For example, Via Flaminia led from Rome to Rimini, Via Appia to Brindisi in southeastern Italy, Via Aurelia from Rome to France, Via Cassia to Tuscany, and Via Salaria to the Adriatic Sea.

Along the main roads, relay and accommodation stations were built every 25–30 km, offering lodging, food, and facilities for changing horses. These stations were usually maintained by residents of nearby villages, which often emerged around them. Along the roads, milestones were placed at intervals of one Roman mile (1,480 meters), marking distances from Rome or major crossroads.

These milestones were cylindrical columns set on rectangular bases, embedded approximately 60 cm into the ground. They stood about 1.5 meters high and weighed around two tons.

Via Appia

Via Appia

The most famous and, in fact, the first Roman long-distance road was the so-called Via Appia. Its significance was underlined by the Roman poet Statius, who wrote: "Appia teritur regina longarum viarum" — "Via Appia is the queen of long roads." It was the first Roman long-distance road built specifically for the movement of military units into areas of conflict with the rebellious Samnites.

The road was commissioned by the Roman censor Appius Claudius, known as Caecus (the Blind). Censors were the highest economic and financial officials of the Roman Republic. Appius also built the first aqueduct in Rome (Aqua Appia) and, in 312 BC, constructed the first section of the road, which still bears his name today. This initial section measured about 200 km and ended at Capua, the capital of Campania. It is believed that Via Appia was the first Roman road paved using lime cement. Around 295 BC, the road was extended by approximately 55 km.

In 290 BC, after the defeat of the Samnites, the "heel" of the Apennine Peninsula was opened to the Romans. Around this time, the road was extended to Venosa, where the Romans stationed a garrison of 20,000 men. After further campaigns, southern Italy fell entirely under Roman influence. Eventually, the Via Appia was extended to the port of Brundisium (modern Brindisi) in 264 BC.

Via Appia beyond the city walls of Rome was also called the "road of tombs" because it was lined with the graves of prominent citizens and wealthy individuals (burials were not allowed inside the city walls). After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the road fell into disuse.

Its restoration was later ordered by Pope Pius VI (reigned 1775–1799). In 1784, a new road — Via Appia Nuova — was built parallel to the old one, running up to the Alban Hills. Many well-preserved sections of Via Appia survive to this day. Tourists can still walk about 16 kilometers of the ancient road from the Baths of Caracalla onward.

Several other sections of Via Appia outside of Rome have also been preserved, and some are still in use today, such as the stretch near Velletri.

Amber Road

The most famous ancient trade route passing through our territory was the Amber Road, which connected Aquileia on the Adriatic Sea coast with the area of today's Gdańsk on the Baltic Sea. Merchants used this route as early as the Late Stone Age (8500 BC – 2900 BC).

Southbound, amber from East Baltic deposits was transported along this route, giving it its name. The route was also used to trade cattle, hides, furs, feathers, and slaves. In the opposite direction, traders carried glass, silver, bronze, and other luxury goods of daily use for that time.

The Amber Road led from the Adriatic Sea through Emona (Ljubljana), Savaria (Szombathely), Carnuntum (near Hainburg), Devín, the Moravian Gate, Wrocław, and Toruń to the Baltic Sea. It was most intensively used from the late 7th century BC to the 5th century AD, with the peak of activity occurring in the 2nd century AD, when it became a key route for long-distance trade within the Roman Empire.

In Slovakia, the main branch of the Amber Road entered through the Devín Gate and ran along the western slopes of the Little and White Carpathians. There was also an alternative route from Bratislava that crossed the southeastern slopes of the Little Carpathians, passed through Čachtice to Trenčín, and then continued via the Vlár Pass towards the main route on the Moravian side.

The road was of great importance as it connected our territory to the global exchange network and introduced advanced ancient culture. Around this long-distance trade route, a network of regional roads was established, creating fixed communication points, including the settlement located within the modern-day cadastre of Senica.

Prehistory of the Bohemian Trade Route

The prehistory of the long-distance trade route, which later became known as the Bohemian Trade Route, begins in prehistory. It was one of the main routes through which a two-way exchange of goods flowed, connecting Western Europe with the East and further to the Near East and Asia.

- The Realm of Samo

- The Great Moravian Axis

- The Přemyslid and Árpád Dynasties

- The Bohemian Queen Constance of Hungary

Prehistory of the Bohemian Trade Route

Prehistory of the Bohemian Trade Route

The prehistory of the long-distance trade route, which later became known as the Bohemian Trade Route, begins in prehistory. It was one of the main routes through which a two-way exchange of goods flowed, connecting Western Europe with the East and further to the Near East and Asia.

- The Realm of Samo

- The Great Moravian Axis

- The Přemyslid and Árpád Dynasties

- The Bohemian Queen Constance of Hungary

The Realm of Samo

Samo was a Frankish merchant born around the year 600. As a trader, he often came into contact with the Slavs and was familiar with the ongoing conflicts and disputes between the Avars and the Slavs. According to the Chronicle of Fredegar, which records this period, it is written:

"The Avars came every year to the Slavs for winter quarters, took Slavic wives and daughters into their beds. Besides various forms of violence, the Slavs also paid tribute. The sons of the Avars, who were born of marriages with Slavic women and daughters, could no longer bear this cruelty and oppression and began to rebel against the Avar overlordship."

In 623, during an anti-Avar uprising, a merchant caravan led by Samo, traveling along the known trade route connecting the Frankish Empire with the Orient, entered directly into the center of the revolt. As every merchant of the time, Samo was skilled in military arts and immediately joined the rebelling Slavs. From Fredegar's Chronicle we learn:

"In the fortieth year of King Chlothar's reign, a man named Samo, a Frank from the land of Senonago, came with many merchants and went to trade with the Slavs..."

Fredegar continues: "When the Slavs attacked the Avars with an army, the merchant Samo fought with them. His great courage and military skills against the Avars evoked admiration and respect. The Slavs, recognizing Samo's exceptional abilities, elected him their king, and he happily ruled for 35 years. During his reign, the Slavs fought many battles against the Avars, whom they always defeated thanks to Samo's wisdom and abilities."

Thus, in 623, Samo became the ruler of a linguistically unified territory when the entire Central and Eastern Europe spoke one Proto-Slavic language.

Fredegar further describes:

"And so it happened that Samo established the first Slavic realm. He later married twelve Slavic women, having twenty-two sons and fifteen daughters with them."

Although Samo is referred to as a "rex" (king) in the chronicle, his realm had a character closer to an Avar khaganate – a tribal confederation. The center of Samo's realm was located in the area of Moravia, Lower Austria, and southwestern Slovakia.

Samo died around 658. There is little information about the further development of his realm. It is assumed that the Slavic tribes separated and began to develop independently. After the fall of Samo's realm, the Avars reestablished control along the Danube line, prompting the Slavic princes to start building their own political centers in Moravia and Slovakia, particularly in Nitra.

The Great Moravian Axis

Along the west-east trade route, two separate principalities were established — the Moravian and the Nitra principalities. When these were unified under the Moravian prince Mojmír, the Great Moravian axis became even more significant. The trade route, as the main axis of Great Moravia, was used by all the important figures of Great Moravian history — the Christian missionaries Cyril and Methodius, princes Mojmír, Rastislav, and even King Svätopluk with their retinues.

Knieža Rastislav víta vierozvestcov Cyrila a Metoda

The Přemyslids and the Árpáds

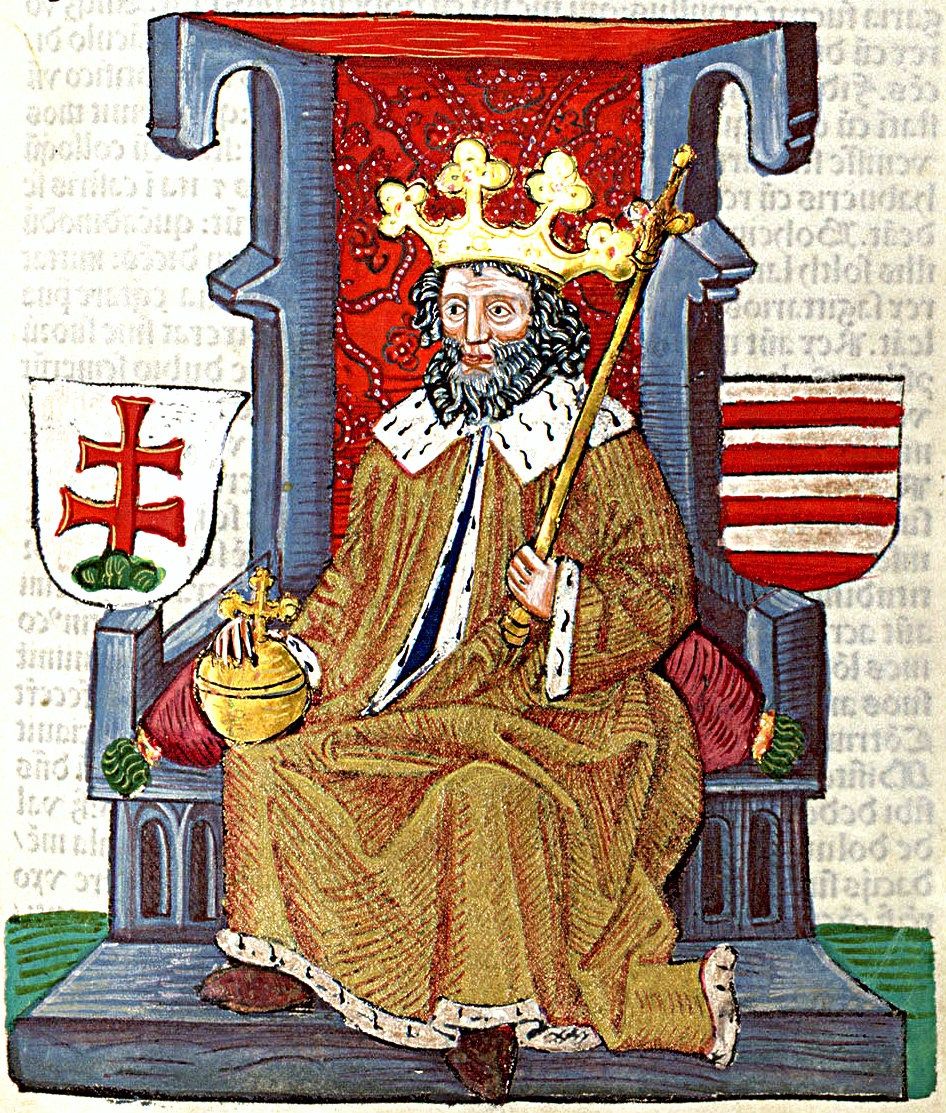

After the fall of Great Moravia, the importance of the trade route declined. The old Hungarians occupied parts of the Great Moravian territory from one side, while the Přemyslids extended their influence along the Morava River from the other. The growth of the trade route's political and diplomatic significance is documented from the 11th to the 12th centuries when it was frequently used for diplomatic-political meetings of Hungarian and Bohemian kings. Several times at the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries, the Árpáds and the Přemyslids met on the Lucko Field (an area located northeast of Hodonín and Holíč). The most famous meetings occurred in 1099, when Czech Prince Bretislav II negotiated with Hungarian King Coloman, and again in 1116, when Czech Prince Vladislav I met with Hungarian King Stephen II. This last meeting ended with a battle in which the Hungarian army was defeated.

Bohemian Queen Constance of Hungary

The traffic on this route intensified again at the beginning of the 13th century when the Bohemian Queen Constance of Hungary, wife of Přemysl Otakar I, received from her father, the Hungarian King Béla III, as a dowry the entire Trnava region between the Little Carpathians and the Váh River. From her husband, she also received the estates in the lower Morava region from Břeclav up to Uherské Hradiště. The Hodonín–Trnava road became the axis of this dominion, connecting Prague on one side and Buda on the other. The importance of the route was underlined by Constance's brother, Hungarian King Béla IV, who established an official toll system along the route.

Porta Coeli kláštor v Předklášteří

The Bohemian Trade Route and its Entry into Written History

Based on the political developments in Central Europe from the 13th century, according to the Vyšehrad Agreement of three kings — Polish Kazimierz III the Great, Bohemian John of Luxembourg, and Hungarian Charles Robert of Anjou — conditions were created in November 1335 for the "promotion" of the existing long-distance trade route connecting Prague with Buda to a royal road. Its "revival" and the establishment of regulations had mainly economic and political goals. It aimed to weaken the Habsburgs and Vienna's economic dominance over long-distance trade. The intention was to strengthen the trade route from Germany to Hungary through Bohemia and Moravia while bypassing Vienna.

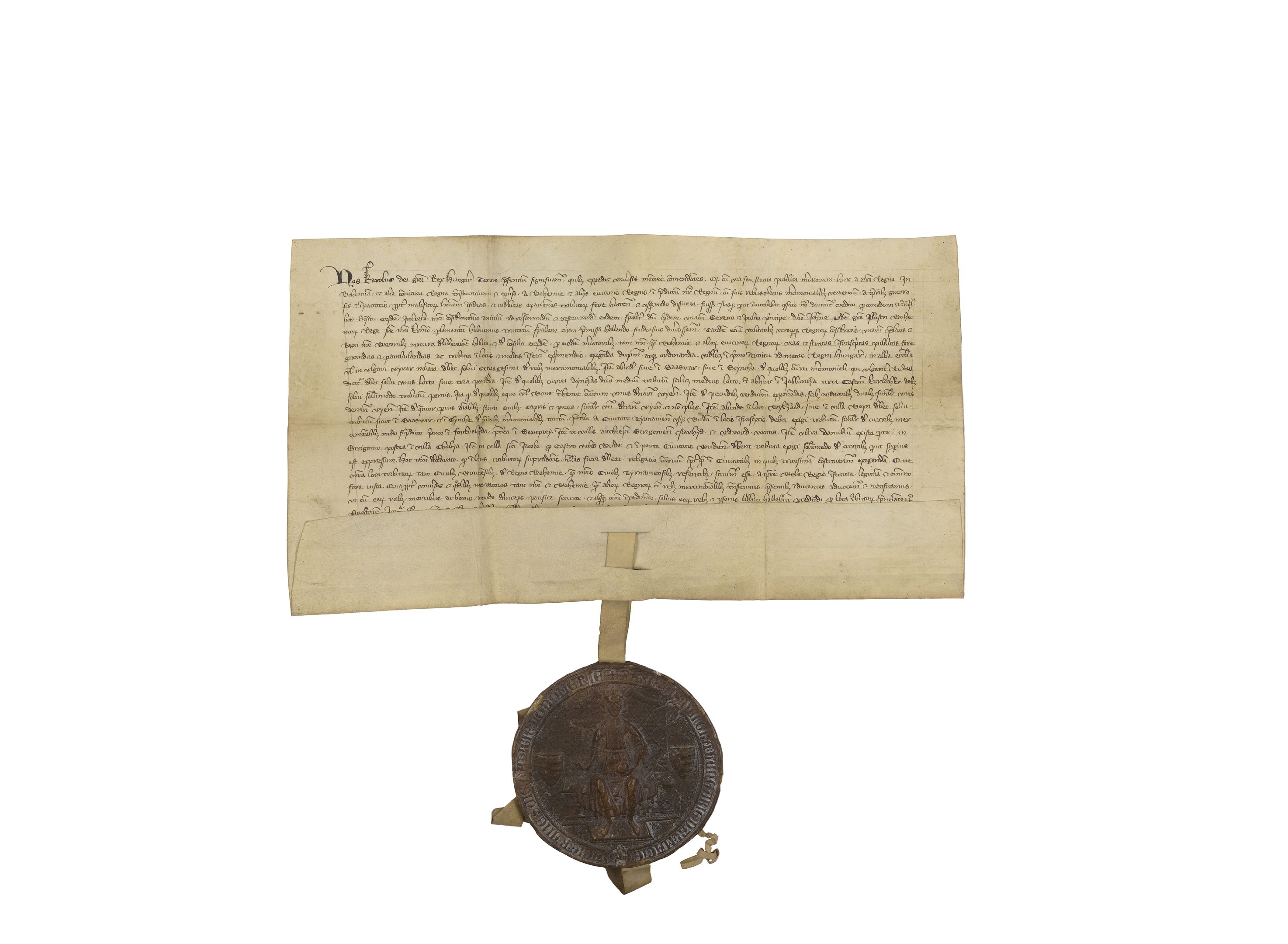

The Hungarian-Bohemian trade agreement was followed by a document issued on January 6, 1336, by Hungarian King Charles Robert, which precisely determined where tolls were to be collected on the Bohemian Trade Route upon entering the Kingdom of Hungary. One of these toll stations was also located in Senica.

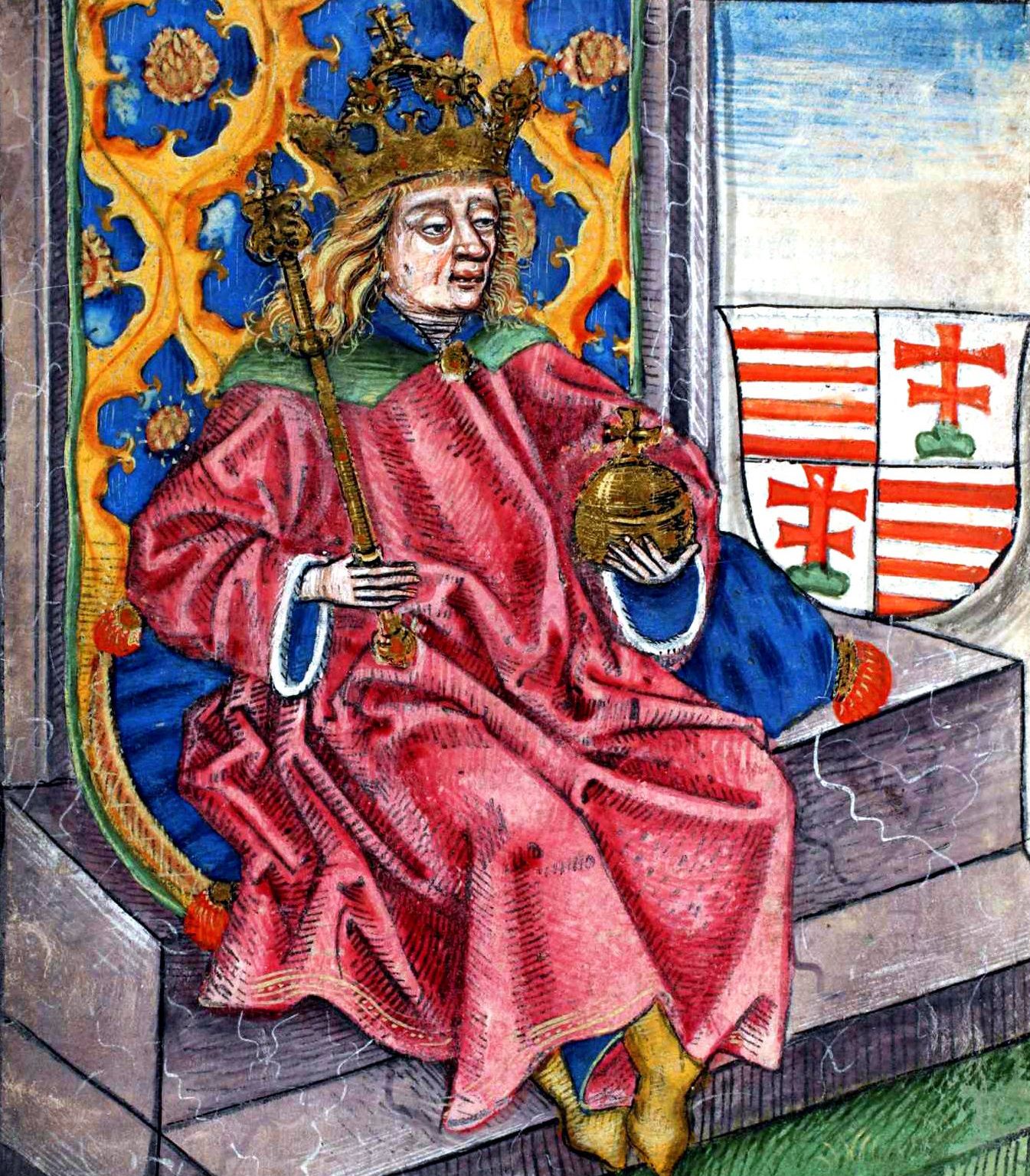

According to merchants from Brno, the decree of Charles Robert reflected the system already introduced by Béla IV (1235–1270). The customs and toll stations mentioned in Charles Robert's charter were, in fact, already established a century earlier by the Árpád king Béla IV, who aimed to economically revive his country after the devastation caused by the Tatar invasion in 124

The Charter of Charles Robert from 1336

Edikt kráľa Karola Róberta z Anjou, ktorým zaviedol poriadok na Českej ceste Listina je uložená v Archíve mesta Brna

Translation

I, Charles, by the grace of God King of Hungary, by this charter make known to all whom it may concern that the public trade route of merchants traveling from our kingdom to Bohemia and other neighboring kingdoms, and vice versa, merchants coming from Bohemia and other neighboring kingdoms into our kingdom with their goods and trade wares, has, due to the dangers of criminals and improper toll collection during times of unrest and wars, been almost entirely abandoned. Since it is our God-given duty to ensure a safer and more peaceful passage for these merchants, we have thoroughly considered repairing and restoring the former condition of this road.

In this matter, we have had discussions with the distinguished and glorious sovereign, Lord John, by the grace of God the enlightened King of Bohemia, our most dear brother, with special attention to the above-mentioned issues. After careful consideration with the prelates and barons of our kingdom and on their advice, we have decreed that this trade route and its connected roads shall be passable and safe. The tolls are to be collected at designated locations and in the manner specified below:

- The first toll within the Kingdom of Hungary is to be paid at Holíč, commonly called Nový Hrad, where eighty denarii are to be paid from the merchant goods.

- Then, at Šaštín or Senica, toll is to be collected from every merchant wagon, called rudas, paying three weights or loads.

- For wagons called ayncza, only half of the toll or half a weight is to be paid.

- At Jablonica near Korlátka Castle, bridge toll is to be collected: one Viennese denarius per horse or ox pulling the wagon.

- Additionally, toll is to be paid for livestock destined for sale: for two large animals, one Viennese denarius; for four smaller animals (sheep, goats, or pigs), likewise one denarius.

- At Buková or Bíňovce, wagon toll is to be collected as in Šaštín and Senica.

From the town of Trnava to Buda, toll shall be collected similarly at:

- Vlčkovce,

- Šintava,

- the villages of the Archbishop of Esztergom: Nyárhíd and Dvory, located beyond the Danube,

- in Ostrihom (Esztergom),

- the village of Csaba,

- the village of Saint James for the old Buda Castle,

- and at the Buda city gate.

No toll shall be collected except where explicitly designated, unless at official tridesimatic (thirtieth) stations.

All these toll stations, known to the merchants of Brno from the Kingdom of Bohemia and our merchants from Trnava, were legally and lawfully established already by King Béla IV.

For this reason, we grant all merchants, both ours and those from Bohemia and other countries, who pass through our lands with their goods, that they may from now on freely and safely, without any obstacles to their health or danger, pass through the specified toll stations.

Therefore, we issue our strictest royal edict to you, Master Stephen, son of Lack, castellan of Holíč, Branč, and Beckov, and also to the count (ispán) of Bratislava Mikuláš called Treutul, castellan of Korlátka and Hédervár, and also to Lawrence Slovák, castellan of Šintava, currently holding these posts and to future appointed officials and castellans. We also request you, Lord Archbishop of Esztergom, together with the prelates, nobles, and other people of any rank holding some of these toll stations, that you ensure, with our highest favor and care, that the mentioned trade route is kept free and passable for the merchants without any obstacles, that they are not harassed or troubled, and that at the mentioned toll stations no higher toll is collected than specified, otherwise you would commit a serious offense against our majesty.

All of this and the mentioned particulars, we wish to be gradually published and proclaimed by you, our faithful and dear servants, at markets and public places in the provinces.

Given at Vyšehrad on the Feast of the Epiphany in the year 1336.

Kráľovská družina na Českej ceste, dobová rytina

Hungarian Coronation Regalia on the Bohemian Trade Route

The Hungarian coronation regalia traveled along the Bohemian Trade Route at least twice. These regalia had significant state-political importance as symbols of sovereign power. After the death of Béla IV in 1270, they were transported to Bohemia under the protection of Přemysl Otakar II (as agreed by the kings). Along with them, several relatives were also sent. Among them was Béla’s daughter Anna, who was the mother of Přemysl Otakar II's wife, Kunigunde of Hungary. Anna secretly carried the Hungarian coronation regalia and a large part of the Hungarian royal treasure from Buda. The sword of King Stephen I, which was part of this treasure, is still kept today in St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague.

The second time, the insignia of royal power were transported under the protection of a large army from Buda to Prague along the Bohemian Trade Route by the Czech king Wenceslas II and his twelve-year-old son Wenceslas III. In 1304, after Hungarian magnates had placed the nine-year-old Wenceslas III on the Hungarian throne three years earlier, Wenceslas II decided, after fierce struggles for the Hungarian throne, that his son should no longer suffer for it. He took the coronation regalia, also as a symbol of state power, with him to Prague, as he did not want to easily give up his influence in Hungary.

The Journey of Treasures on the Bohemian Trade Route

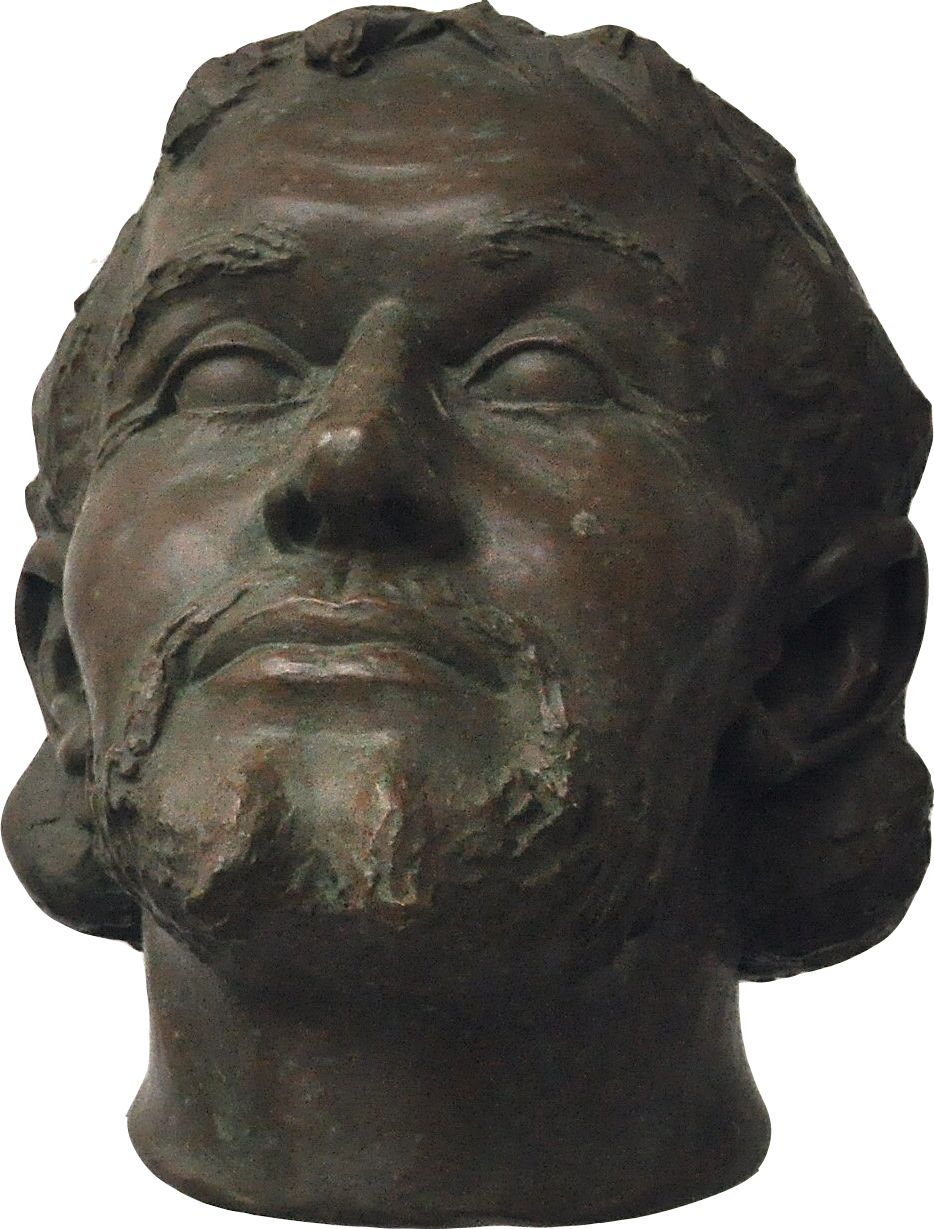

Since the Bohemian Trade Route was a merchant's road, merchants moved along it daily, carrying with them almost fairy-tale-like riches. In times of danger, especially during wars, they often hid their treasures directly along this route. These treasures were only a fraction of what was transported along the Bohemian Trade Route as part of royal convoys (many were discovered centuries later). One of the most notable historically documented journeys along this route was the passage of the court of King Matthias Corvinus.

The Bohemian Trade Route witnessed the pompous journeys of King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, who traveled repeatedly between Moravia and Buda. One of the most famous was his journey to Olomouc in 1469 for his coronation as King of Bohemia, elected by the Catholic nobility. For the celebratory feast, which took place after the coronation, he brought from Hungary precious kitchenware made of gold and silver, valued at 200,000 gold coins.

In 1475, Matthias transported from Brno to Buda, accompanied by a large army, a treasure worth 1,250,000 ducats in gold. During his diplomatic negotiations with King Vladislaus II in Olomouc in 1479, he is said to have brought along treasures allegedly equaling the value of the entire Kingdom of Bohemia.

The Bohemian Trade Route — The Road of Diplomats

Besides its commercial and military importance, the Bohemian Trade Route also served as a route for diplomatic communications. Couriers traveling between Prague and Buda were an almost daily phenomenon. Messages concerned preparations for military campaigns, their progress, mutual assistance, or peace negotiations.

Hussite delegates traveled this road to negotiate with King Sigismund in Buda, Belgrade, Bratislava, and Skalica, depending on his location. Negotiators representing George of Poděbrady and Matthias Corvinus also moved along the route. In 1465, the Olomouc and Várad bishops resolved a dispute that arose between them using this road.

The Road of Knowledge and Solidarity

The Bohemian Trade Route was not only a commercial and cultural highway but also a carrier of knowledge and shared values. Cultural values and education spread along this route. The economic reforms introduced by Charles Robert of Anjou and later continued by his son Louis I the Great required skilled officials. During their reigns, 73 educated Czechs served as officials of the Hungarian state.

Between 1367 and 1420, 155 students from Hungary studied at Charles University in Prague. Remarkably, 34 of them came directly from settlements located along the Bohemian Trade Route. The steps of these "knowledge-seeking" young people towards Prague and their ties to the university were largely carried out via this route, especially since the Viennese inquisitor bishop of Passau created obstacles for students traveling to Prague through Austria.

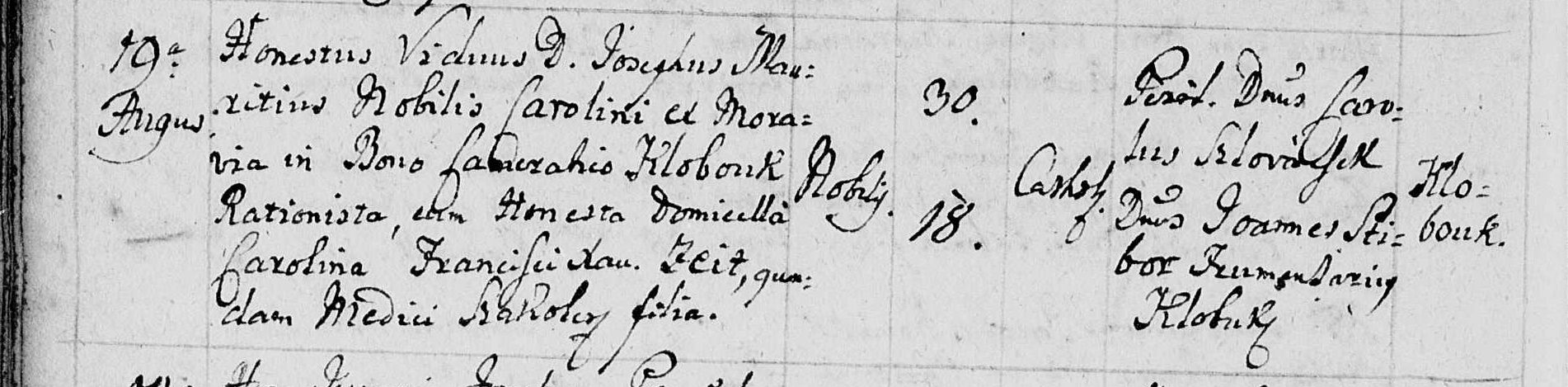

The Bohemian-Slovak Bond

After the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), three major waves of Hungarian exiles moved along the Bohemian Trade Route. The first came immediately after the Battle of White Mountain, the second around 1627, and the third at the end of the Thirty Years' War. A large part of these refugees from Bohemia, Moravia, and Austria settled in western Slovakia, notably in villages along the Bohemian Trade Route. This period brought about the blending of populations, later reinforced through natural fluctuations due to economic or family reasons. This is why we can trace, even in the oldest preserved registers, inhabitants whose roots lie in Bohemia or Moravia based on their surnames.

The Bohemian Trade Route maintained Czech-Slovak and Moravian-Slovak interconnectedness. Through trade and movement along this route, new family ties and bonds were created. This affected not only the nobility but also the broader population. International marriage bonds are recorded in many church registers. The Bohemian Trade Route was also significant for the Reformation, as the first Protestant congregations and Evangelical churches of the a.v. (Augsburg Confession) were established along it, with communication centers in Holíč, Skalica, Senica, and Sobotište.

The national awakening of the Slovak nation was also closely linked to the towns along the Bohemian Trade Route, where the influence of the Habsburg Enlightenment was significant. The estates of Holíč and Hodonín became, in the 18th century, under Francis Stephen of Lorraine, family property of the enlightened monarchs Maria Theresa and Joseph II.

Sobáš šľachtica Jozefa Maurícia, účtovníka z Klobouk s Karolínou Zeitovou, dcérou skalického lekára rok 1817

The Young Slovak Intelligentsia and the Bohemian Trade Route

The youngest generation of Slovak intelligentsia, which took over the baton of the national revival movement in the mid-19th century, frequently used this famous route. In July 1843, Ľudovít Štúr, Michal Miloslav Hodža, and Jozef Miloslav Hurban traveled along this route to visit the national awakener and poet, the Catholic priest Ján Hollý at his parish in Hlboké, to receive his blessing for the finalization of the new codified form of the Slovak written language. The mutual solidarity between the Czech and Slovak nations and their connection via the Bohemian Trade Route were also evident during the founding of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918. Although the Provisional Government of Slovakia used a train, it still followed the path from Prague through Brno, Hodonín, and Holíč to Skalica. The Bohemian Trade Route thus witnessed Slovakia's incorporation into the Czechoslovak Republic.

The Bohemian Trade Route – A Dangerous Military Road

The significance of the route, both positive and negative, is confirmed by current archaeological finds. In 26 locations in Slovakia directly on or near the Bohemian Trade Route, numerous and valuable hoards of coins have been discovered, dating from the Celtic period up to the early 18th century. Among these were Spanish coins, Bavarian coins, Hanseatic and Polish coins, Pomeranian coins, and numerous Czech groats, Viennese denars, and even Jewish coins. These hoards are linked to the dangers faced along the Bohemian Trade Route, as it was not only goods that moved along it but also various military groups and armies, which did not respect any regulations, even those established by King Charles Robert of Anjou.

Besides traders, the inhabitants of towns and villages directly on or near the Bohemian Trade Route also suffered during times of war and military movements.

Hungarian kings often used the Bohemian Trade Route during military campaigns aimed at occupying parts of Great Moravia. Conflicts between the sovereigns of the divided Czech and Hungarian kingdoms were often resolved by military operations that took place along the Bohemian Trade Route.

The dangers of warfare were already known since the times of the Přemyslid and Árpád dynasties. One example is the well-known siege of Holíč Castle by the armies of John of Luxembourg in 1315, or the occupation of the Holíč and Branč estates by Austrian troops, which held them for a long time.

Hrad Branč – detail rytiny J. van der Nypoorta z r. 1686

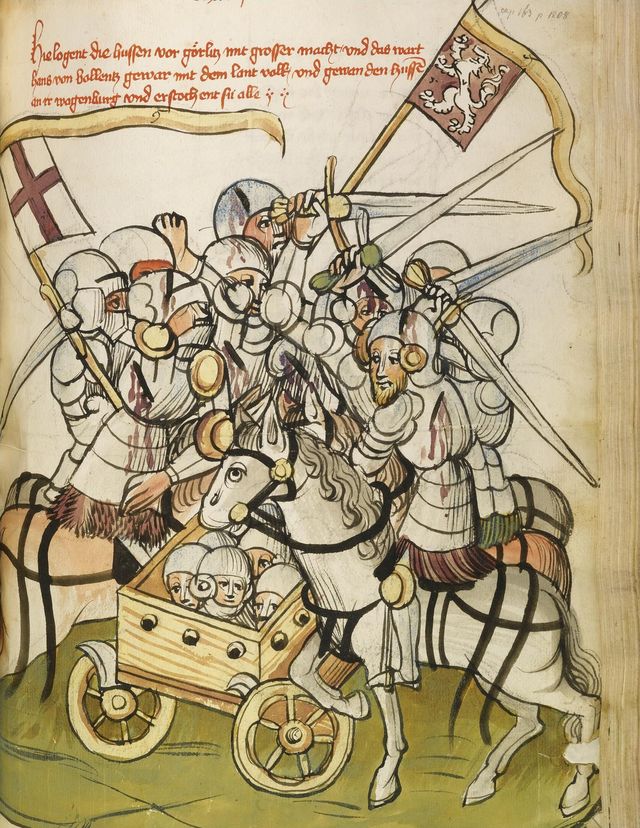

The Hussite Period on the Bohemian Trade Route

The Hussite revolution, which demanded a far-reaching reform of the Church between 1415 and 1436, significantly affected the Bohemian Trade Route. The period of Hussite presence in this region, marked by their "expeditions," left deep scars on the towns and villages situated along the route. The Hussites first appeared on the Bohemian Trade Route according to B. Varsik in 1423, when, under the leadership of Jan Žižka, they broke through Skalica and Trnava to southern Slovakia, where they plundered extensively. In 1428, Prokop the Great with his army ravaged not only Holíč but also the surroundings of Trnava and the suburbs of Bratislava. At the end of March 1430, after crossing the Czech-Hungarian border, they reached as far as Trenčín, where they clashed with the Hungarian army near Šintava. The result was 6,000 Hungarian and 2,000 Hussite casualties.

The Hussites devastated western Slovakia again in 1432, when they occupied Skalica and Trnava permanently. These free royal towns remained under Hussite control until 1435. The Hussite raids caused massive destruction in Slovakia, destroying many churches, monasteries, and burning numerous towns and villages.

Anti-Habsburg Uprisings and the Bohemian Trade Route

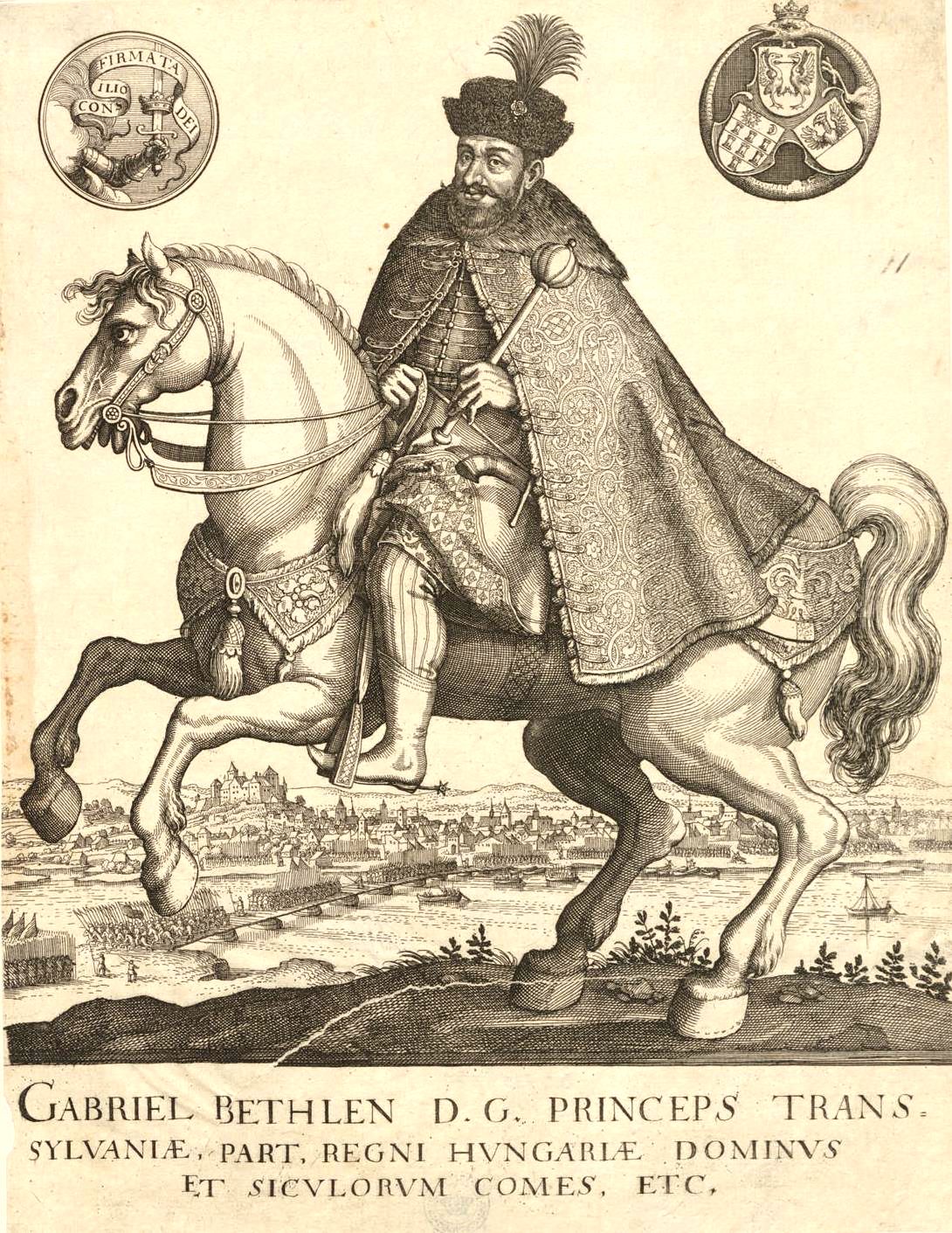

The Anti-Habsburg Estate Uprisings were armed revolts of Hungarian and Transylvanian estates against the Habsburgs and their absolutist-centralizing efforts. The second such uprising, led by Transylvanian prince Gabriel Bethlen and supported by Turkish troops, reached the Bohemian Trade Route in 1619, occupying towns in western Slovakia and Moravia along the route. Other forces, including those of Juraj I. Rákóczi, in 1644, advanced from Transylvania into eastern Slovakia and later, in 1645, crossed western Slovakia along the Bohemian Trade Route to assist the Swedish army besieging Brno.

In 1663, Turkish troops passed along the Bohemian Trade Route, burning down not only Senica but also smaller villages and proceeding into Moravia, where they continued looting.

The last Anti-Habsburg uprising to affect the population living along the Bohemian Trade Route was the uprising of Francis II Rákóczi between 1703 and 1711. His troops occupied the Trenčín, Bratislava, and Nitra counties, and in May 1704, they crossed the White Carpathians to Jablonica and continued to Vrbovce. A new wave of Kuruc rebels reached the area again in 1706. Near Brezová, these rebels suffered defeat in a decisive battle against the imperial army. Only the Peace of Szatmár in 1711 ended this unrest and brought the much-needed peace to the residents along the Bohemian Trade Route, although the traders and merchants who regularly used it had suffered much.

The Battle of Austerlitz and the Bohemian Trade Route in Action

Začiatkom decembra 1805 sa uskutočnila bitka troch cisárov, v ktorej pri Slavkove neďaleko Brna porazil Napoleon Bonaparte spojenú rakúsko-ruskú armádu. Česká cesta slúžila ustupujúcim a zdecimovaným rakúsko-ruským vojskám ako úniková.

At the beginning of December 1805, the famous Battle of the Three Emperors took place, where near Austerlitz (Slavkov) near Brno, Napoleon Bonaparte defeated the combined Austrian-Russian army. The Bohemian Trade Route served as an escape route for the retreating and decimated Austrian-Russian troops.

The Austro-Prussian War and the Bohemian Trade Route

The Austro-Prussian War of 1866, which decided the leadership within the German Confederation, ended with the defeat of the Austrian army at the Battle of Königgrätz (Hradec Králové). The retreating Austrian troops used the Bohemian Trade Route. The same route was used by advancing Prussian units pursuing the Austrians.

The population along the Bohemian Trade Route had to provide food supplies to both armies and fulfill transportation demands — often using their own wagons at the expense of their regular agricultural work. During these forced supplies, the Prussians frequently plundered and looted. Eventually, cholera broke out among their ranks, which then spread to the local population, killing hundreds of local inhabitants.

Provisional Government for Slovakia and the Formation of Czechoslovakia

In 1918, the provisional government, based in Skalica, carried out military operations to incorporate Slovakia into the newly formed Czechoslovak Republic. Troops marched from Skalica and Holíč along the Bohemian Trade Route towards Senica and continued through Biela hora all the way to Trnava.

Provisional Government for Slovakia and the Formation of Czechoslovakia

Provisional Government for Slovakia and the Formation of Czechoslovakia

The Bohemian Trade Route under Protection and Maintenance

As early as 1336, King Charles Robert of Hungary issued an edict instructing all castle captains along the Bohemian Trade Route and royal officials, both current and future, to ensure the safety and proper maintenance of the route, making it passable and usable. A quote from the edict reads:

"... and by this edict, we command that you are obliged ... to maintain the route free of any obstacles for the merchants, so they may pass safely, ... for otherwise you would commit a grave offense against our majesty."

Zrúcaniny hradu Ostrý Kameň

Maintenance of the Bohemian Trade Route

Since the formation of the Bohemian Trade Route, guard castles along its length ensured order and protection. A special group was tasked specifically with the responsibility for the route's maintenance and passability. In mountainous areas such as the Little Carpathians, nature itself often played a role — falling gravel and debris hardened the roadbed, while fords across rivers and streams required regular repairs and upkeep. When water levels were too high to cross, ferry services or rafts were used.

Similarly, sections of the road that became marshy during rainy periods had to be made passable with simple construction techniques. Raised causeways were built using woven willow barriers and layers of earth. Prehistoric and early medieval roads often avoided these risky areas altogether by following elevated terrain. During the Middle Ages, to save time and effort, travelers began to cut distances by crossing these lower-lying sections directly, which led to the development of rest stops and roadside facilities. Some of these evolved into important points along the route, while others lost their significance over time.

A major innovation came with the creation of enclosed road spaces separated from fields and meadows by hedges. In 1554, a living hedge is mentioned in a document dividing the Holíč-Šaštín manor estate, which ran between Holíč and Šaštín along the royal road (the Bohemian Trade Route). The road was also equipped with drainage ditches to carry away rainwater.

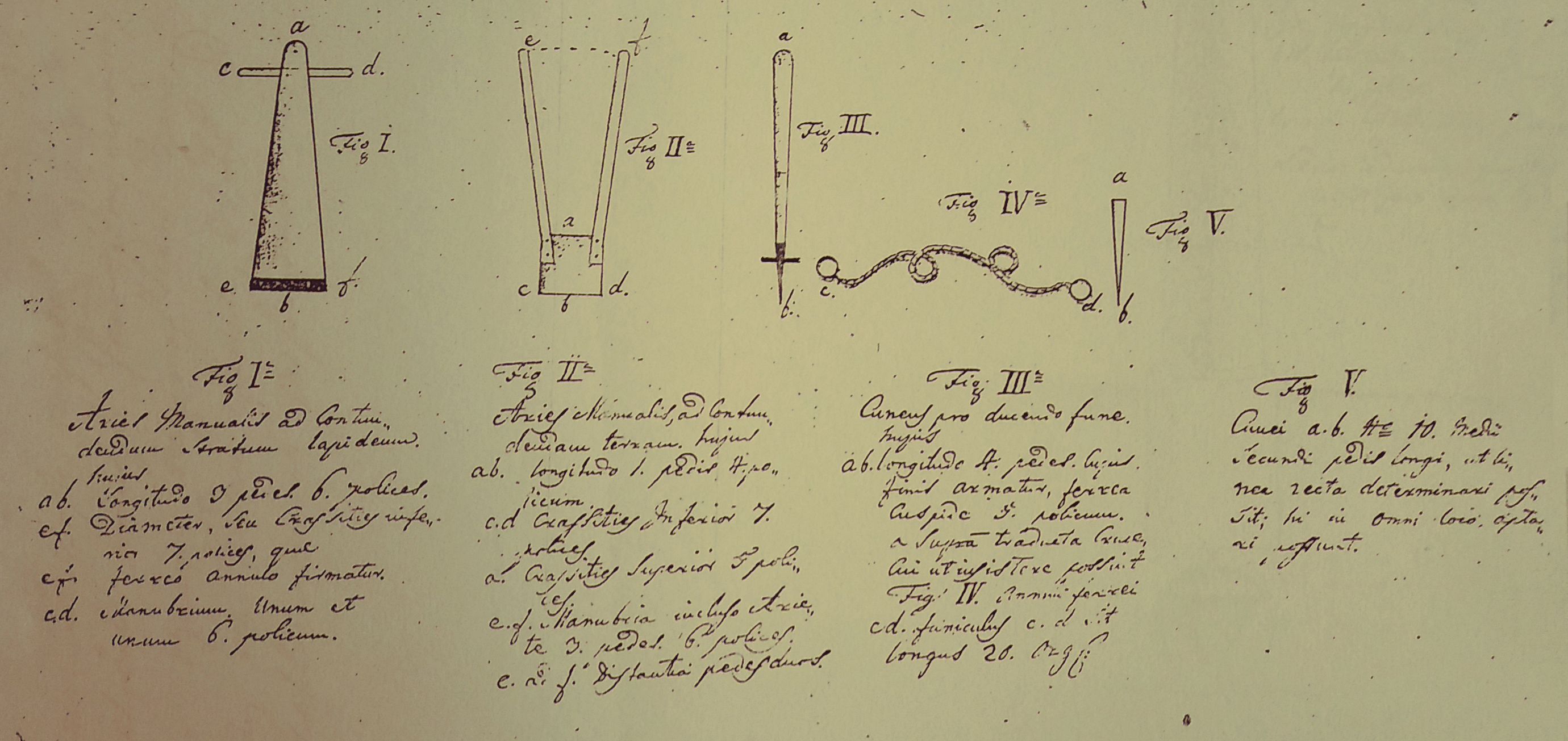

„Manuál“ na výrobu nástrojov na údržbu ciest

County Administration Takes Over Road Maintenance

From the early modern period onward, especially concerning international routes, maintenance of roads increasingly became the responsibility of county administrations (župy). The central Hungarian government pressured local governments to ensure the functionality and upkeep of long-distance routes. From the 18th century, the most important royal roads and other vital communication lines — economic, military-strategic, and postal — were singled out for special attention.

These roads fell under the supervision of the Royal Vice-regency Council, representing both the ruler and regional authorities. Edicts regarding road and bridge repairs on royal roads were issued for the Nitra County in 1717 and for the Bratislava County in 1716 and 1720, confirming this obligation.

The Royal Vice-regency Council's 1744 call for road repairs in Bratislava County specified that roads had to meet the increased requirements of a modernizing army. Specialized military units, especially artillery, needed roads and bridges that could support their equipment. Thus, military parameters became part of the design.

County technical staff — engineers and surveyors — inspected roads, prepared documentation, and produced instructions, guidelines, and tools to assist in road construction and maintenance. Guidelines were also issued for signage and the placement of direction posts and distance markers along these roads.

The Story of the Bohemian Trade Route Continues

The Bohemian Trade Route was an extraordinary phenomenon in the past. People who walked along it shaped Central European history. The town of Senica, for example, owed much of its growth and prosperity to this route. Although the name itself faded into the background during the 19th and 20th centuries, its importance and role never truly disappeared. Its function as the main commercial artery was eventually taken over by the highway connecting Prague and Bratislava (today part of the IV. Pan-European Corridor: Berlin / Nuremberg – Prague – Bratislava – Budapest – Thessaloniki – Istanbul).

The original Bohemian Trade Route underwent significant technical and technological transformations, just like the means of transport that travel along it to this day. After the split of Czechoslovakia in 1992, the route regained its international importance and still lives on today, connecting Prague, Brno, Trnava, Štúrovo, and beyond. The Bohemian Trade Route is alive even in the 21st century.